A couple of weeks ago,

of Serengenity made a salient comment (emphasis added) on my post about great-great uncle George’s 1911 Callin Family History:In that time period Genealogy was quite a fad, consequently many are badly written and poorly sourced. Their resources at the time included interviews with oldsters in the family and connecting through genealogy want ads in newspapers. So much of it is backed by the collective memories of the oldest memories of the family. The purpose of those books was not facts and truth, it was the creation of the families' origin story.

As we learn more about our collective family history, we inevitably learn more about the mythology America’s European colonizers built around their experiences. And it is important to keep in mind what mythology means, because “myths” are not simply “true or false.” When they are the stories we tell about ourselves, they can incorporate facts, capture elements of our self-image and of our aspirations, and they can shape the way we interpret which parts of the stories are factual.

A Callin/Callen Family Myth

For example, the 1911 Callin Family History and The Callen Chronicles, published in 1990, both include what appear to be different versions of the same story. I discussed both stories on the old Mightier Acorns blog in “The Perils of Polly (or Margaret),” where you can read them side-by-side.

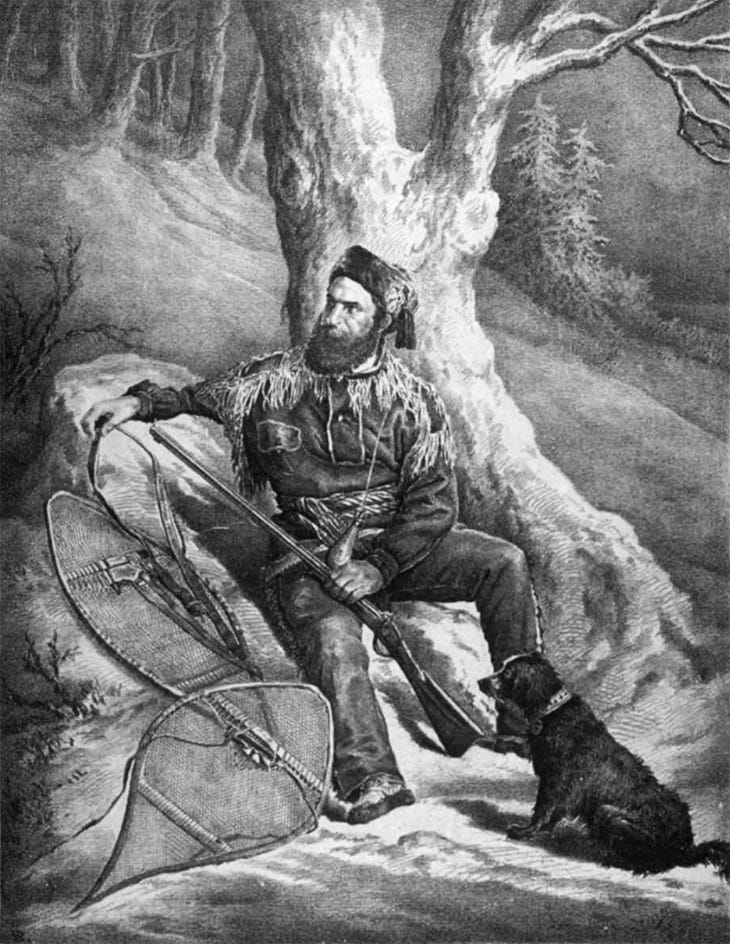

In The Callen Chronicles, the story is that the twin daughters of Patrick Callen, about six years of age, were taken from his home in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, during a raid by hostile Native Americans. One of them returned to her family after a white trader (one of those mythical frontiersmen) came to the village where she and her sister had been living for about 12 years.

The story George Callin recorded tells of Polly, a daughter of James Callin, who was taken in a raid, presumably from his home in Westmoreland County. In that story, James summoned a posse, which chased down the raiding party and recovered Polly, who was permanently injured in the ensuing fight.

Determining which parts of these twin stories are “true” is challenging. The account in The Callen Chronicles contains more details, including a mention of the relationship between Margaret (the twin who was recovered) and Patrick Callen’s grandson, Watson. It is also a less dramatic story, told in a way that sounds more factual, although neither story has any facts that are likely to be verifiable by research. My theory is that the Patrick Callen version of the story is probably “true” and that the version told about “Polly Callin” was altered and adapted as George’s grandfather and great-uncle retold the story to their children in Ohio, and was further adapted by those children when they told the story to their children.

Framing this story as part of a larger American Mythology has nothing to do with whether or not it is “true” and everything to do with how the people telling the story felt about it. And in the story of the stolen daughters, the people telling the story felt threatened by an outside invader…even though, strictly speaking, they were the outside invaders.

James Callin, Indian Fighter

I still don’t have enough evidence to make a proof argument connecting my Ohio ancestors to the Revolutionary War veteran named James Callin, whose military career I have written about before:

So far, my research amounts to speculation about who my 5th-great-grandfather might have been, and if he was this person, I further speculate that the story told about Patrick Callen’s daughters was turned into a story about James Callin’s daughter as James’s descendants created the family’s origin story.

I have to acknowledge that I am continuing to create that origin story. Even if I can find evidence to prove that the brothers who settled in Milton Township, Ohio, in the early 1810s, James and John Callin, were the sons of the Revolutionary War soldier named James Callin, all of this is still part of the mythology recorded by George and the Callen researchers.

As I learn more about our history and try to trace my ancestors’ place in it, I can see why the story of these girls was necessary to the mythology built up around our family. Because without this dramatic tale of being attacked in our homes and having our vulnerable children snatched away by “invaders,” James Callin would have no honorable reason to join General Scott’s Kentucky cavalry and be a part of the war to push Native Americans out of the Ohio Territory.

Whether James claimed the story of Polly as his own, or (more likely) he repeated the story of what happened to Patrick’s family to his children and grandchildren, it became a part of the family’s mythology: a self-image of ourselves as victims fighting back against a terrifying threat. And our fear of that threat was used as part of a broader campaign to make us part of the United States’ plan to expand westward.

Our Family Origin Story

Whatever the specific facts may prove to be, my version of that family origin myth currently says:

“Our Callan ancestors came to North America from Ireland. In Ireland, they suffered from increasing oppression from their British neighbors and the violence and economic hardship brought on by centuries of religious conflicts. In America, they were caught between hostile factions of English and French colonizers who allied with warring groups of indigenous Americans at different times for different reasons.”

The Callans seem to have justified the part they played in displacing Native Americans from their homes by pointing to a specific raid that harmed and terrified them, and they have passed that story down for generations.

James Callin probably chafed under the Quaker government of Pennsylvania, as the pacifist Quakers and the British government were unwilling to provide soldiers or arms to defend the people living along the front lines of the French and Indian Wars. That could explain why he enlisted with a Virginia Regiment when Virginia sent recruiters through Westmoreland County, PA (which, at the time, Virginia claimed as Yohogania County), and that would explain how he ended up serving under General Scott.

Later, in 1794, when James likely joined the Kentucky cavalry to fight under Gen. Scott again, Gen. Scott had personal reasons for wanting revenge on the Shawnee people from Ohio who had killed his son. The need to see himself as defending his family, rather than framing himself as a genocidal aggressor, could explain how James’s descendants transformed a story about the raid on Patrick’s family into a raid on their own.

And that is how, despite whatever the facts might be, a myth is born.

The Power of the Modern Myth

Here in America in 2025, we tell ourselves similar stories to justify our actions. Americans whose ancestors came from around the globe to live here have become the native population that fears outsiders. I can’t help noticing that our fear of them probably has more to do with what we did to the indigenous people of North America when we were the outsiders than it does with any supposed actions by modern immigrants. Most of the stories we tell ourselves capture how we feel rather than reflecting the facts.

Too many Americans seem willing to accept lies about being “invaded” by people from other countries, and listen to men calling for an end to what they call “open borders”—a myth that ignores how the open borders between our states drove our unity and economic growth after the completion of the railroads in the 1880s and after World War II.

Too many Americans feel the economic disparity caused by decades of income inequality and buy into the idea that, because resources are scarce, we must accept further economic austerity and cruel policies towards our most vulnerable neighbors—a mythical argument that doesn’t hold up under the weight of historical evidence.

Our record of learning from our past and seeing through misleading myths is not great. Few of our average citizens are willing to do the hard work of figuring out what is and isn’t true, and prefer to embrace a version of their story that justifies their part in whatever they have already decided to do. If we’re lucky, we will still be here to recover after the consequences of their choices play out, and we’ll get to tell a more accurate version of their story.

When James Callin and his children told themselves their origin myth, they couldn’t have known the scale of the atrocity they were committing. To them, the continent was vast, and they were the underdogs. But by 1910, when George wrote his history, the brutal treatment of the Native Americans was mostly complete, and the establishment of America as a rising world power included a “cowboys and Indians” myth as part of our national image.

When George recorded his version of the family origin story more than a century after his grandfather’s time, he didn’t have many facts and accepted the version of the story that justified the family’s place in America. Now, more than a century after George, I still don’t have many facts and must do the best I can to tell our story.

I can only hope that in another century, researchers will find my work and that it will help them understand why we told that story.

In personal experience family myths fall into one of several categories: 1. The attempt to insert ones own life into the family history in a twisted or invented narrative. 2. To obfuscate or hide a family scandal 3. To perpetuate a grievance, usually concerning stolen land, lost inheritance, etc.

Thank you for this thoughtful piece. Many of the points raised here connect directly with what I’ve been trying to do in my own family history writing. I’m based in Australia, and as I trace the lives of my convict ancestors and their descendants, I see similar patterns — especially in how suspicion of outsiders and decisions about who belongs have shaped communities.

One moment that stays with me comes from the life of Robert Anthony, an Irish teenager who arrived in Australia seeking a better future. He is my great-great-grandfather. By his late twenties, he had found employment as a turnkey inside a prison in Toowoomba, then still very much a frontier town in Queensland. Just before taking up his post, he witnessed a public hanging of two men — one Aboriginal, one Chinese. Both had committed crimes, and they were hanged side-by-side, but the image stays with me as a symbol of how harshly outsiders were judged. The irony, of course, is that the Aboriginal man was no outsider to this land at all.

Your writing speaks to these issues clearly and carefully. I’m glad I came across your work and will be following with interest.