“If it bleeds, it leads.”

Newspapers are a valuable resource for family history research. I frequently incorporate newspaper articles (often obituaries) into my WikiTree profiles. Newspapers helped me tell the story of when Martin Callin was killed in 1889:

However, newspapers were never meant to be a permanent record, and while we love to romanticize the importance of a free press to a democratic society, we must never lose sight of the primary reason newspapers exist: to make money.

That means that the truth of a story is less important than the sales it might generate; and if the audience has a strong bias toward one narrative, the reports that make print are likely to be shaped by that bias. Then, as now, the more outrage a story can generate, the better.

Martin Callin’s uncle Marquis

Marquis Callin was the son of Thomas Callin and Nancy Burgett, born about 1833 in Ohio. After his father’s death, he may have been apprenticed outside his mother’s home in 1850. He was in Olivesburg, Richland County, Ohio in 1860, a 27-year-old shopkeeper listed as “Munfer Callan” living in the household of his brother, a shoemaker named Thomas Jefferson “Jeff” Callin. Jeff Callin was the father of Martin Callin from “A Tragic Wealth.”

Marquis was named in the 1911 Callin Family History, but it was only in 2020, after years of looking, I found evidence that told me where he went after 1860. (If you enjoy details, see the old Mightier Acorns blog essay, “The Price of Progress: An Update”.)

The 1870 Census record for Wauseon, Fulton County, Ohio, listed Marquis under the name “Martin”—fortunately, the 1880 Census listed Marquis in Wauseon by the correct name. With wife, Caroline, and elder son Fred in the household on both records, I am comfortable asserting that the “Martin” in 1870 was a clerical error.

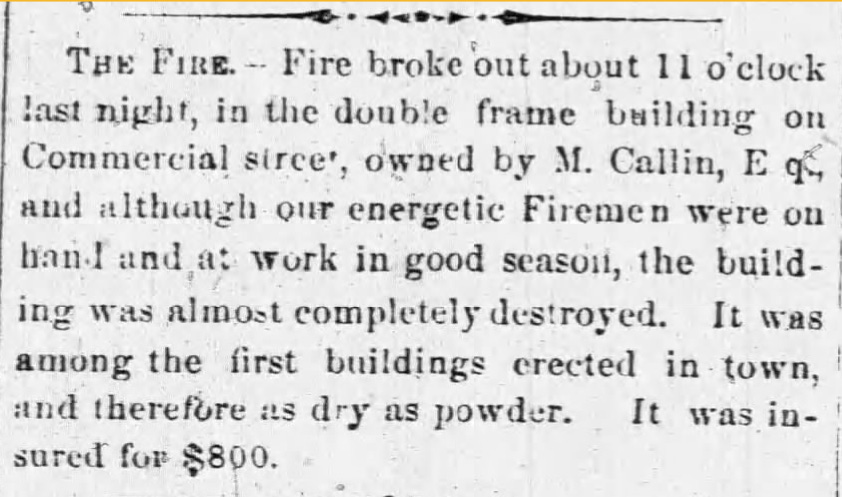

But because his nephew Martin was a well-known businessman before his 1889 death, I have to carefully judge records attributed to “M. Callin”—especially in newspapers—because they could refer to either Martin or his uncle Marquis. I’m pretty sure this one refers to Marquis, because Martin would have only been 17 at the time, and unlikely to own a building:

After the loss of his building, Marquis did not make the newspapers again. The entirety of his Callin Family History biography is: “Born 1840, died in Chicago, date not known.” The most recent evidence we have of his life is the 1880 Census placing him in Wauseon. If he did die in Chicago, I have found no other evidence of it.

The Factual Records

We know that Marquis and Caroline were married about 1865, and we know from his father-in-law’s will that he and Caroline (née) Snyder, had two sons: Fred and John. We see their family in Wauseon in 1870 and 1880 when Caroline is noted as suffering from an unspecified lung disease. She died in 1880, probably after the 8th of June when the census was enumerated, and she is buried in Wauseon Union Cemetery.

As far as the solid evidence of census and vital records goes, that’s all I have to connect Marquis to his sons, but thanks to the flawed and sensational reporting of the 1890s, I have enough clues to find at least one of his sons in later records.

Two Callin Boys Go to Court

On August 30, 1890, Fred S. Callin was arrested in Seattle, Washington, for stealing $1,000 in gold coins from a canvas sack containing $5,000 belonging to the Western Express Company. The thief had cut a hole in the seam of the sack, taken the money out, and sewn the hole back up, and the theft had gone undetected for a week. Fred was a freight clerk working aboard the S.S. Idaho, a sidewheel steamboat that ran on the Columbia River and Puget Sound from 1860 to 1898.

The arrest was reported by the Associated Press and printed in The Los Angeles Times on 31 August. The AP account described Fred as “a young man scarcely 21 years of age” and refrained from making any assertions about Fred’s guilt or innocence. But The Post-Intelligencer in Seattle showed less restraint in their 31 August report. After saying that the “dapper young freight clerk” was arrested, they state “The evidence against the prisoner, who is scarcely 21 years of age, is very clear and his guilt is almost proven.”

The Post-Intelligencer goes on to describe the theft and the investigation in detail, and ends their piece with this prejudicial paragraph:

This is not the first time the young suspect has been summoned involuntarily to answer to charges in the couris. A short time ago he was arrested with two girls in the Occidental hotel on Pike street, the tenor of the main complaint having been kept quiet. It was known, however, that the trio were in a beastly state of intoxication, and were beld to answer on a serious charge of vandalism.

On Monday, 1 September 1890, the Spokane Chronicle weighed in under the headline “A Smooth Freight Clerk.” Once again, “a dapper young man, scarcely 21 years of age” was arrested, and after describing the crime, the paper asserts:

When the robbery was discovered the young clerk's movements were shadowed, and the authorities claim that there is not the slightest doubt as to Callin's guilt.

The Post-Intelligencer reiterated the strength of the case against Fred on 3 September, quoting Deputy Sheriff Woolery:

Captain Woolery said: "No, we don't want any more evidence; we couldn't have any more; it's conclusive."

The crime was also reported on 3 September in The Anaconda Standard in Anaconda, Montana. Their objective reporter repeated the claim that “The evidence against the prisoner, who is scarcely 21 years of age, is very clear and his guilt is almost proven.” They added this opinion: “The circumstances under which the money was lost are peculiar and shows [sic] the job to have been done by a nervous and bungling hand.” Obviously, they did not agree that Fred was a “smooth freight clerk.”

On Saturday, 6 September 1890, The Post-Intelligencer reported on the opening of the trial:

Callin came into court, occupied a chair near his attorneys, Wiley and Scott, and during the hearing stroked his light moustache and appeared perfectly cool and unconcerned.

Taking up several column inches of Page 5, the report quotes several witnesses giving testimony, and describes them as “reticent” or otherwise unwilling to “divulge anything” - but reading the statements, it becomes clear that the case was built on the idea that Fred was seen spending a lot of extra cash after the robbery occurred, and that nobody actually saw him with more than three or four $20 coins in his possession.

For all of the buildup and coverage, I was unable to find any reports of the verdict—at least not in 1890. But we finally get to see what happened in Fred’s story when John gets arrested in 1892:

The day before, The Post-Intelligencer had reported that John Callin was charged in Tacoma with grand larceny for taking $35. Once again, they seem convinced of his guilt, stating, “He was locked up in the city jail. Callin is about 18 years old and seems to realize his position keenly.”

This time, though, we get to see the outcome, and The Post-Intelligencer’s editor is clearly miffed by it. Under the unbiased headline, “Newsboy Callin Goes Scot Free,” we learned that Justice Von Tobel dismissed the charges after the complaining witness, Daniel McFail admitted “that there was a partnership between himself and the boy,” leading the justice to declare that the defendant could not be prosecuted for grand larceny.

A Happier End for Jack Callin

Given the events that placed Fred and John Callin in Seattle, I looked there for evidence of their lives after the 1890s. Fred seems to disappear completely after his trial, but John shows up during the 1900s in both Seattle and Alaska, where he went into the restaurant business.

Eventually, Jack Callin, proprietor of the Arcade Cafe in Valdez, Alaska, married Nina Gifford of Seattle in 1913. He made the papers when he installed electric heaters in the cafe in February 1916, and again when the cafe burned down in January 1917. Jack moved into other business endeavors, establishing an automobile dealership in Anchorage by 1918, the Callin Motor Company, which he was still running in 1930.

Nina died in May 1938, and Jack appears to have left Alaska to live in the Seattle area after that. He married again on 9 December 1938, and he and the former Edith Ferris lived in Hillcrest, King County, Washington.

He died on 12 May 1940 and was buried with Nina in Lake View Cemetery in Seattle.

It’s impossible to tell from these sources whether he led a happy, crime-free life, but at least we get glimpses of his story. And those glimpses remind us to take every source with a grain of salt.

Bias is something we don't necessarily consider unless we have different accounts of a situation mentioned in a newspaper article. I have some English press cuttings of court cases from the 1920/30s collected by my great grandfather and they make for very interesting reading. Each newspaper has a different view of the proceedings. I have scanned some of them and at some point will probably publish an article or two about them.

This is something I have been thinking about a lot as I've been doing some research in the Reconstruction era. Then, much like now, the country was incredibly polarized politically. It can be really difficult to try to suss out the truth from newspaper accounts of anything during that time, even if I use sources from both "sides".