Family Music: The Accordion

Inter-cultural ties to the larger family tree

If you’ve been following my new music newsletter, All Kinds Musick, you may have noticed my recent post about the Los Lobos album, La Pistola y El Corazon. In it, I said:

I credit [David Higaldo’s] work on this album as the final puzzle piece that made me accept the accordion as a favorite instrument instead of seeing it as just an oddity. This journey took me from Weird Al’s parody polkas through the Pogues and into Zydeco records. The instrument also features so prominently in these Latino traditions, that I began to wonder how it got there.

There is a good answer to that.

The accordion was first developed in the 1820s by Viennese and German instrument makers.1 It was inspired by a centuries-old Chinese instrument called the “cheng” or “sheng” introduced to Europe in the 1770s by a Jesuit explorer. The addition of bellows and Western-style keyboards allowed players to make chords with one hand while playing a melody with the other, and various designs spread quickly throughout Europe and the rest of the world. German immigrants brought the instrument with them when they settled in Texas in the 1840s along with styles like polka, waltzes, the “schottische” and mazurkas.2

The Tejanos who lived in Texas incorporated this music into their own culture, sometimes replacing guitars with accordions and setting the corridos they wrote to tunes that were built around these new European styles. After only a couple of generations, the music that came out of this fusion was strongly associated with Tejanos and Mexican musicians to the point where the descendants of the German immigrants forgot their own cultural ties to it.

My own German immigrant heritage is a small part of my family tree. The only German immigrants I have traced back to Germany were Joseph Frey and his wife, Elizabeth Horn, who probably arrived in New York in the 1840s from their birthplaces in the Duchies of Baden and Hesse. I do have German heritage in older lines who arrived in North America much earlier.

The Witter and Piper (or Pfeiffer) families appear to have been in Pennsylvania by the mid-1700s, and their descendants married into the Tice (or Theiss) family that arrived slightly before them.

The Shriver and Cline families that ended up in Kansas probably came from Germany before 1800 and also lived in Pennsylvania for a few generations.

Elizabeth Berlin’s family almost certainly arrived before the Revolution and lived on the Pennsylvania/Maryland state line.

And we just finished reading about Hessian soldier Leopold Zindle!

German ancestry can be tricky, because the nation of Germany didn’t exist until 1870, and the fiercely independent states that formed it had been part of the Holy Roman Empire for a thousand years before the Napoleonic Wars put an end to that in 1806. Cultural identity as “German” did exist, but people tended to define themselves by their religion or by their language before “nations” became common, and it can be difficult for us to look back now and sort out who “belonged” to the numerous shifting populations that lived in Europe.

The United States struggled to figure out how to integrate its English-speaking and German-speaking populations in its early years. Benjamin Franklin wrote of the German-speaking settlers in Pennsylvania after he began serving in the Pennsylvania legislative assembly:

"Few of their children in the country learn English; they import many books from Germany... The signs in our streets have inscriptions in both languages, and in some places only German. They begin of late to make all their bonds and other legal writings in their own language, which (though I think it ought not to be) are allowed good in our courts, where the German business so increases that there is continual need of interpreters; and I suppose in a few years they will also be necessary in the Assembly, to tell one half of our legislators what the other half say."

In other places, he wrote about the impossibility of mixing the two cultures. He contrasted the German standards of beauty for their wives against that of the English in terms which, if he were saying them about Latinos today, would have likely scuttled his political career.

He also turned out to be wrong about the permanence of the divide between the two cultures. Today, the German language barrier is all but forgotten, except that many Americans have very long surnames that are hard for people to spell. The anti-German sentiment that rose during the two World Wars seemed to drive many families to ignore or deny German heritage. One unfortunate facet of this assimilation process seems to be that people descended from German immigrants forgot so much about what was good, and adopted some bad habits from their English neighbors - like Mr. Franklin.

The good news is that despite the blinkered view that one group is somehow “superior” to another, the wild diversity of musical traditions - or of one’s ancestry - is never entirely out of reach. People will make the bonds and connections that are important to them, and then later generations can sort out and promote what they value. For my part, I’ve learned that I value this instrument more than I thought I did - and I can thank my buried German heritage for its existence!

And if you love All Kinds of Musick, visit:

Accordions Worldwide, “The Accordion and its History”

Moras, David, Journal of the Life and Culture of San Antonio, “The San Antonio Origins of Conjunto Music”; University of the Incarnate Word.

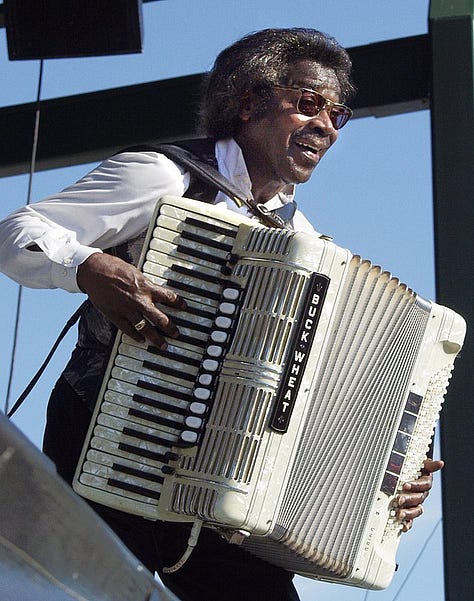

Flaco Jimenez photo: By Tony 1212 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62492556

Very interesting!

My grandfather used to play the accordion. I never heard him play, though. Sadly, he sold it on a rainy day.

Huge accordion fan myself and not sure I can blame my German heritage for that or not. Donna the Buffalo puts the accordion into roots rock for me. The best bumper sticker I ever saw? I love accordion music and I vote!