Oh everyone believes

From emptiness to everything

Oh everyone believes

And no one's going quietly

John Mayer, “Belief”

Religion is a tricky thing to wrap your mind around. A person’s faith is both a personal, private thing and a public signifier of how they think about moral and spiritual issues. Each of us has a set of beliefs, a moral code, and traditions that we observe - and sometimes learning about the religion of an ancestor can give you insight into what that person was like.

In the right context, knowing a person’s religion can tell you things that you need to know about them, as a genealogist, such as “how and where they were buried” or “how and why they were married.” Those are external behaviors, though. The tricky part is understanding the internal feelings that inform or come from a particular person’s faith in that particular time and place.

As a family history researcher, you need to be aware that your assumptions about religion might give you a false picture of what your ancestors’ lives were like. When you find an obituary that declares a person was a “staunch Christian,” you can’t assume that because you also consider yourself a “staunch Christian” you share the same beliefs, or that they would make the same choices you would make.

Think about how diverse attitudes in your own religious community are towards things like divorce, alcohol, or tolerance of political dissent within the community. Your ancestor’s “staunchness” doesn’t tell you anything about which side of a given issue they would have been on.

Maybe you do the math and see that a baby was born far too soon after the wedding date. In many/most other cultures, that date discrepancy might signify that the marriage became necessary after the pregnancy was discovered - and could indicate hard feelings between in-laws. There are also communities and situations where this might have been ignored or even encouraged by the community.

Consider the Oneida Community that existed in upstate New York from the mid-to late-1800s. They formed at the end of the Second Great Awakening, which gave rise to many new religious movements in the United States, such as Adventism, Dispensationalism, and the Latter Day Saint movement. The Oneida famously practiced group marriage, lived communally (in the sense of communal property and possessions), and practiced “male sexual continence” - a concept I won’t go into here, but which is not typically associated with “Christian mores.”

Granted, most of us won’t find roots in the Oneida community. (I do have a “mother-in-law of 4th cousin 2x removed” who was named “Freelove” and was born in 1846, but that only shows that the Oneidas weren’t alone in holding that particular value.) But you will find ancestors who belonged to faith traditions that regard each other as heretical, backward, apostate, or just plain “weird.” And you will have to be on guard not to draw incorrect conclusions about them.

You will be well served to treat “religion” the way you would treat the size label on a new pair of shoes - the label may tell you what the size is supposed to be, but you don’t know that they will fit until you try them on and walk around for a bit.

Just for one example:

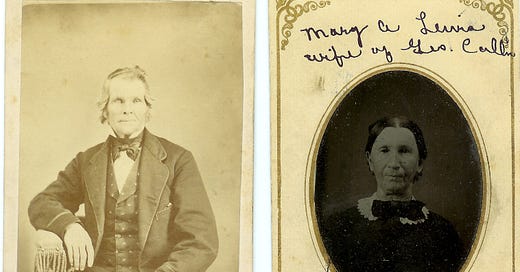

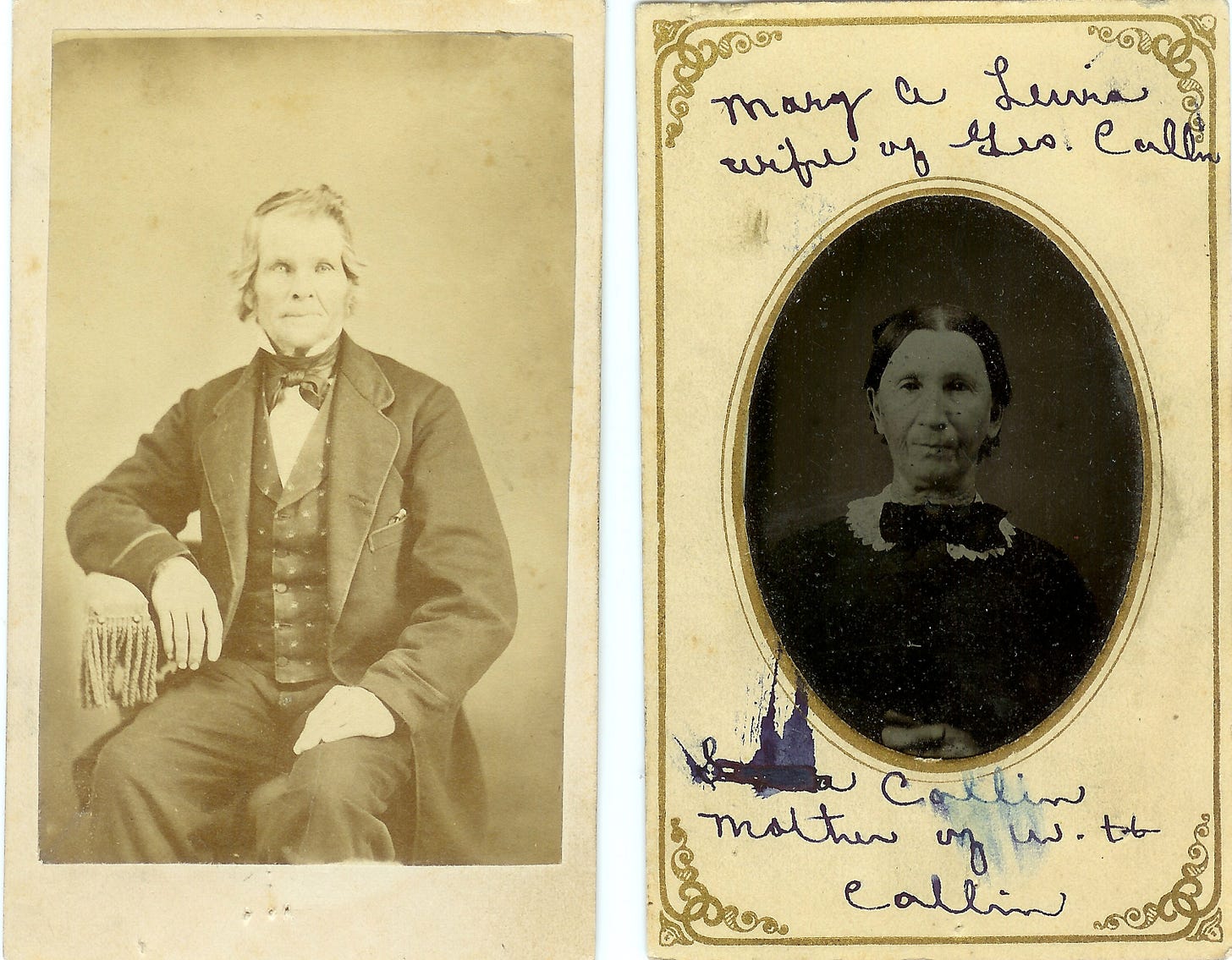

My 3rd great-granduncle, George Callin (1804-1879), was described to me by a cousin who is directly descended from him as “a strict Presbyterian” - implying they were opposed to alcohol consumption and the use of profanity. Meanwhile, another source referred to George’s ancestors as “hard-drinking Scots-Irish Presbyterians,” which on the surface seems contradictory.

Another source - written by the daughter of George’s nephew, Rosemary Callin - emphasized this memory:

“Father said they were warned not to say nothing at school about it, but their cabin was a station on the Underground Railway. I don't know whether it was William or Elizabeth, probably the latter, who awakened them softly in the middle of the night and led them to the window. The moon flashed out and they saw a white man, maybe William, leading a string of blacks through the clearing around their cabin and into the woods. They were on their way to Great Uncle George's barn. From there he would take them onto the next stop.”

When you dig into the history of Presbyterians and abolitionist movements, you can see evidence that convictions among members ran the gamut from openly opposing slavery to defending a “moderate” approach to releasing slaves from bondage. But among those who were strong abolitionists, you could see other patterns emerge, as well.

Abolitionism, temperance and prohibition movements, and women’s suffrage were all deeply linked.1 It seems likely that since George, and probably his wife, Polly, were associated with abolition activism, and their descendants remember them for being sober, you might be safe in assuming that they were part of a community that supported all three reform issues.

While you would not be correct in assuming that anyone remembered as a “strict Presbyterian” would necessarily support any of these movements, knowing that George was involved in at least one of them can give you some insight into how George’s faith looked to him. To break the law and take the risks associated with transporting escaped slaves through Ohio in the 1840s showed a deeper commitment than simple belief.

Ultimately, a person’s religion doesn’t dictate what kind of person they are or were. Just as your religion is more often a reflection of how you see yourself and how you want to live, your ancestor’s stated faith gives you clues to how they thought about themselves and their place in the world. If you use what you know about a specific faith to prompt questions about the ancestor who practiced it, you can learn a lot about their motivations and their views that you might get from a few words in an obituary.

Just don’t jump to conclusions. As Paul said in his first letter to the Thessalonians:

Test all things; hold fast what is good.

In this context, “good” means “supported by evidence.”

National Park Service, NPS.gov, “Abolition, Women's Rights, and Temperance Movements”

Thought provoking.

Spot on!