As I have conducted my family history research over the years, I have had to go back more than once and reconsider my biases.

Like anyone else, I tend to think of my point of view as “neutral”—but it rarely is. My point of view was shaped by the culture I grew up in and by the relationships I have with other people. As I learn more about American history, I must adapt my thinking and correct for the biases I was taught.

Sometimes, I have been guilty of over-correcting. While trying to avoid projecting one set of biases onto the data, I may project a different set of biases. Sometimes this over-correction is an important and intentional academic exercise. For example, when writing about the European settlement of the Eastern United States, it is easy to find resources that record the point of view of those settlers—but it is very difficult, if not impossible, to find any written records of the people they displaced.

To correct for that bias in the written records of history, one must challenge the assumptions and biases of those who wrote the records and sometimes speak on behalf of people who are no longer here to speak for themselves. That can be risky and can provoke people who are invested in maintaining the notion that their point of view is a true or neutral one.

The Reactionary Party Line

When provoked by a threat to their self-conceptions, people often argue out of ignorance of the available facts, and they may claim that attempts to understand and correct biases are, in fact, the real mistake. They will reach for a ready-made term for this—another explicit bias that has dogged scholars under many names for as long as scholarship has existed.

I was a cynical 20-something in the 1990s when a wave of backlash against what was called “political correctness” swept through pop culture. It was a loaded term then, and it has stayed a loaded term - along with ideas about “the PC police” and more recently “woke” culture.

None of this is new. Before the term even originated, Americans were practicing political correctness:

The original meaning of “politically correct” arose from post-revolutionary Russia, when adherence to the Communist party line often meant accepting things that were not true as facts. The idea was that saying that you accepted non-factual things as fact kept you from being shot or imprisoned. George Orwell’s book, 1984, captured the idea of “Doublespeak” and spurred countless middle schoolers in the late 1980s and early 1990s (hi! It’s me!) to start second-guessing things they were told by people in authority.

More modern understandings of the term look more like this:

political correctness (PC), [is a] term used to refer to language that seems intended to give the least amount of offense, especially when describing groups identified by external markers such as race, gender, culture, or sexual orientation.

The irony here is that this shift in meaning is, itself, a form of political correctness.

Trends in the U.S. towards greater individual freedom and equitable inclusion in society for women, people of color, and religious and ethnic minorities culminated in the Civil Rights legislation of the late 1960s. But that historical moment also fed into a backlash in which the majority of the population—usually white, usually men—cast themselves as victims being targeted by “the state” for expressing mere opinions.

Even though few, if any, laws exist to police or punish “offensive” speech, we are expected to accept the counterfactual argument that giving offense is a crime. And even though America has a well-documented history of terrorism against those pushing for equal rights between the end of the U.S. Civil War (1865) and the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1965, many specific events—like the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, Wounded Knee—are treated as if they don’t exist for the sake of “not offending” people who might be uncomfortable discussing them.

Unfortunately, much about our shared history is uncomfortable.

Why We Are Talking About This

Discussing the violence that accompanied the rise of labor unions, the removal of Native Americans from their land, and the struggle to correct the fundamental moral error of allowing slavery is—and should be—central to any historical research. The fact that violent events occurred is undeniable. Sometimes our ancestors were involved, and the role they played may or may not sit well with you now.

However, discussing violence of any kind is always disturbing, and many people cope with it by disassociating it from themselves or their ancestors. This is a bias that is baked into the stories Americans have told themselves about their origins and their heritage. Confronting that bias is rarely something that people are willing to do.

I am in the process of learning everything I can about my ancestors. My 5th-great grandfather, James Callin, is a major focus of my research. Most recently, I wrote about his possible association with military units that fought to drive the original Native American inhabitants from what is now Ohio:

When researching the battles he might have been present for, I ran across material like this:

The Battle of Fallen Timbers was the culminating event that demonstrated the tenacity of the American people in their quest for western expansion and the struggle for dominance in the Old Northwest Territory. The events resulted in the dispossession of American Indian tribes and a loss of colonial territory for the British military and settlers.

National Park Service, Historical Overview of Fallen Timbers Battlefield and Fort Miamis

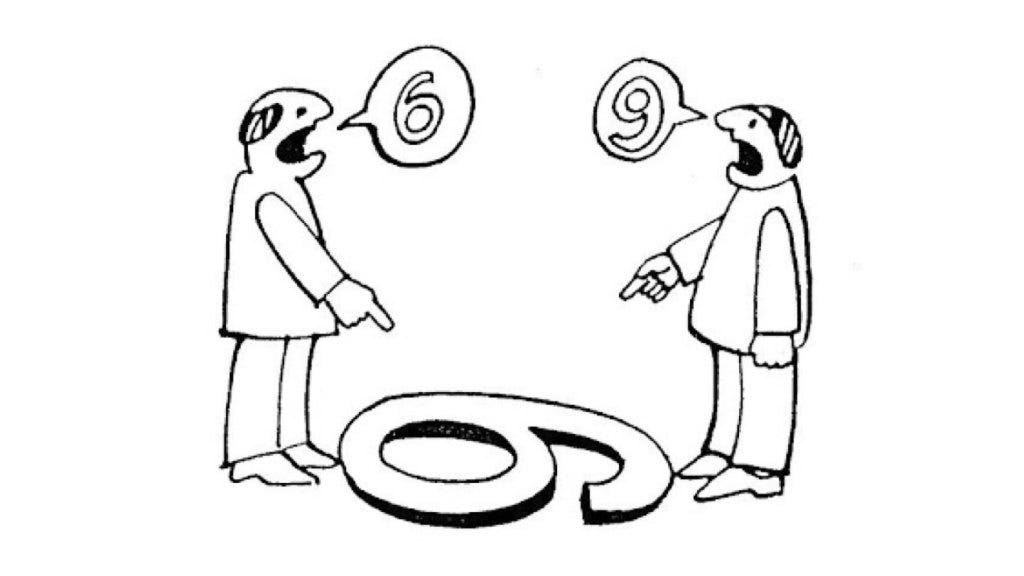

As a human being, I know I have a baked-in bias toward viewing events like this through a binary lens—two sides, with one victor and one loser—but the reality of that moment in history is that there were multiple “sides” and motivations were as numerous as the participants. In 1794, the British were still trying to destabilize the new American government and were using allies among the First Nations to do it. Tecumseh (Shawnee) and Chickasaw leaders were recognized for helping the U.S. forces and protecting them from the British side.1

Framing the Battle as “the culminating event that demonstrated the tenacity of the American people” is not a neutral statement. Tenacity is usually seen as a positive characteristic. That framing casts the “American people” as the “good guys” while acknowledging that their tenacity was in service of expansion and dominance. But dominance is the thing that our foundational myths tell us we were fighting against—and acknowledging that our quest was for dominance undercuts our self-image as the righteous underdogs.

For many people, that is an uncomfortable thing to live with.

Sticking to Facts

The pursuit of any kind of “neutral” point of view is impossible, but we still try to understand the facts. Understanding the violent events that accompanied the building of the railroads and the establishment of America as a global power in the late 19th century is a necessary part of understanding my family history. So is the relationship between abolitionist sentiments and segregationists; or the slower push for suffrage and gender equality. But I don’t always have direct evidence of the part individual ancestors played in the larger history - and that means challenging family lore and treasured stories and rethinking the way we cast our ancestors as “heroes” or “villains.”

There is a good-faith debate to be had about what political correctness is, and when it is appropriate for one group of people to insist that another group of people change the way they speak or act. But I find that people often use that newer definition of “political correctness” I listed above to derail discussions that make them uncomfortable. Challenging a person’s sense of who their ancestors were is one of those discussions.

Objecting to “political correctness” also implies that the idea you are being forced to accept is not a fact.

And facts are what we are trying to establish.

Chickasaw.tv (website of the Chickasaw Nation): The Battle of Fallen Timbers

The idea of politically neutral institutions and media is a 20th century one and not something our ancestors would have acknowledged at all. In Pennsylvania until the 1910s, newspapers clearly stated their alignment with a political party or business interest and each county had several of each. Thank goodness for diversity in thinking and recording history.

Indeed, when were we EVER neutral? Thank you for raising the point and reminding us to pay attention to the perspective of every source we draw from.